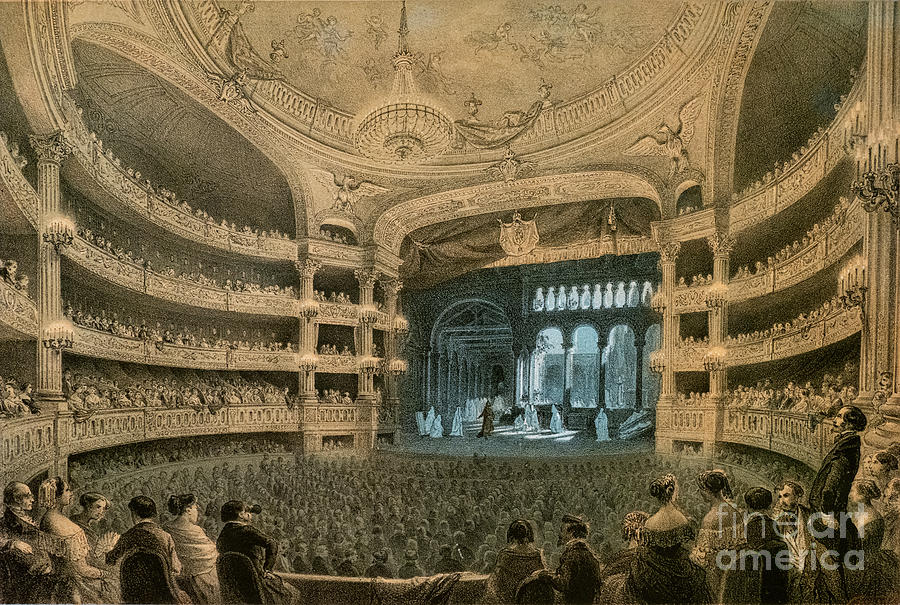

Theatrical artwork

Your YouTube followers want to feel connected to you, so you must take every opportunity to build your channel’s brand. Let Desygner become your YouTube Banner Maker, and customise your profile with photos and text that best describe your videos Lucky Tiger online casino. The more personality your channel has, the more people you will attract.

Yes, the AI-generated cover photos created using Venngage’s tools are copyright-free. You can use them for both personal and commercial purposes without any restrictions on copyright. However, it’s always good practice to ensure that any externally sourced content you include is also cleared for use.

Want to showcase your love for travel, art, or a favorite hobby? Or maybe you want to project a more professional image? Our tool allows you to customize your cover photo to match your vibe. It’s quick, easy, and ensures your profile makes a lasting impression.

Enhance your LinkedIn profile with a polished, tailored cover photo that aligns with your professional image. Showcase your expertise and set the tone for your profile with a design that speaks to your career achievements.

Theatrical artwork

Playing on the notion of adventure and curiosity, David Teniers the Younger’s A Guard Room inspires a sense of innocence in its viewer while creating tension within its “stage” of events. The piece depicts a child exploring a guard house, very likely outside of adult supervision. The décor of the armor suggests it is used for military ceremonial purposes, further increasing both the playfulness and impending consequence of the boy’s presence. The theatrical nature of this piece plays on the actions of its subjects combined with a stage setting very suitable for mischief. Dynamic shadows are used to create a depth in the piece, furthering the sense of space in the manner that a theater stage is laid out. Certain portions are hidden from the viewer for the purposes of the subject. Just as a director would in a production, Teniers only shows you what you need to see to understand what is happening in the piece. Though more elaborate than some of the other examples, even the wide shot of the guardhouse can be thought of as being somewhat conservative, playing on the unknown to further the sense of mischievous adventure.

Everyone can recognize the look of the theater stage. The lighting is dynamic with sharp contrast, the figures are starkly illuminated, and almost everything is exaggerated in some way, whether in costume or in gesture or both. The theatre carries a wonderful notion of story-telling and imagination with it that creates a framework for imagination. The dark curtains and raised platforms of the stage create the illusion that scenes that play before the viewer are in fact real, and that the audience is merely intruding on a story that would have happened regardless of whether or not they were listening in. This, to me, is the essence of the stage. In a sense, nearly all artistic arrangements of figures within a piece draw from the same principles that make up the ways in which a director would position actors within a scene. Paintings of interactions between people can be created to have an almost cinematic feel, drawing from that same notion that what is happening within the image would happen by itself, regardless of whether or not the viewer was there to see it. These images aren’t static; the events depicted are motion-oriented, and the viewer is almost always left wondering what might happen next within the scene. These works in particular create their own “stages”, where some of the details of the locale are shrouded through tenebrism or infinite space, placing more importance on the figures and their implied actions. This gallery is a collection of Renaissance and Baroque paintings that depict events happening within their own stages, alluding to the idea of being in theater.

In a theatre production, the hierarchy of roles from the director to the stage manager orchestrates the ensemble of actors and actresses to breathe life into the performance. The theatre company encompasses a collection of individuals, each with specialized tasks, managed and unified by the director to achieve a coherent vision.

Playing on the notion of adventure and curiosity, David Teniers the Younger’s A Guard Room inspires a sense of innocence in its viewer while creating tension within its “stage” of events. The piece depicts a child exploring a guard house, very likely outside of adult supervision. The décor of the armor suggests it is used for military ceremonial purposes, further increasing both the playfulness and impending consequence of the boy’s presence. The theatrical nature of this piece plays on the actions of its subjects combined with a stage setting very suitable for mischief. Dynamic shadows are used to create a depth in the piece, furthering the sense of space in the manner that a theater stage is laid out. Certain portions are hidden from the viewer for the purposes of the subject. Just as a director would in a production, Teniers only shows you what you need to see to understand what is happening in the piece. Though more elaborate than some of the other examples, even the wide shot of the guardhouse can be thought of as being somewhat conservative, playing on the unknown to further the sense of mischievous adventure.

Everyone can recognize the look of the theater stage. The lighting is dynamic with sharp contrast, the figures are starkly illuminated, and almost everything is exaggerated in some way, whether in costume or in gesture or both. The theatre carries a wonderful notion of story-telling and imagination with it that creates a framework for imagination. The dark curtains and raised platforms of the stage create the illusion that scenes that play before the viewer are in fact real, and that the audience is merely intruding on a story that would have happened regardless of whether or not they were listening in. This, to me, is the essence of the stage. In a sense, nearly all artistic arrangements of figures within a piece draw from the same principles that make up the ways in which a director would position actors within a scene. Paintings of interactions between people can be created to have an almost cinematic feel, drawing from that same notion that what is happening within the image would happen by itself, regardless of whether or not the viewer was there to see it. These images aren’t static; the events depicted are motion-oriented, and the viewer is almost always left wondering what might happen next within the scene. These works in particular create their own “stages”, where some of the details of the locale are shrouded through tenebrism or infinite space, placing more importance on the figures and their implied actions. This gallery is a collection of Renaissance and Baroque paintings that depict events happening within their own stages, alluding to the idea of being in theater.

Cinematic artwork

With an almost chameleonic effort across the film’s set design, all the visual cues are set in place to transport us to a Hollywood that no longer exists… The music, like the cars, have only aged for better. Punctuating the plot, a certain Paul Revere & The Raiders record gives us a glimpse into Sharon Tate’s private life. With the first few notes of “Good Thing,” we see the actress played by Margot Robbie start to feel the groove; a rare glimpse into the personal routine of someone at the height of their fame. As she’s bobbing her head, L’automne by Alfons Mucha can be noticed in the background. Through her tastes, both musical and artistic, and art in movies, Sharon Tate becomes more than just a two-dimensional character or actress, she becomes a person.

Quentin Tarantino’s latest movie is a cinematographic love letter to the Hollywood of the 60s. In this self-reflexive tale, we’re met with reality-inspired characters such as Sharon Tate, along with other, more fictional ones, like Rick Dalton or Cliff Booth. Throughout the film, Tarantino makes an art of weaving the new and the old, the real and the fictional.

Through Baz Luhrmann’s modern interpretation of a literary classic, many have wondered if historical accuracy is all it’s made out to be. As with previous examples, when we find art in movies it’s rarely accidental. Usually, it’s there to serve a specific purpose. “Baz had no overt desire to modernise The Great Gatsby. Rather, he wanted modern audiences to understand how modern the Gatsby world felt to its protagonists at the time,” shares Catherine Martin, the film’s set director.

Spanning three decades in the life of the eponymous character, viewers are presented with a feature length homage to Edward Hopper, which also explores the culture and zeitgeist of mid-twentieth century America. With incredible attention to detail, thirteen of Hopper’s paintings are brought to life in this extraordinary indie film by director Gustav Deutsch, and cinematographer Jerzy Palacz.